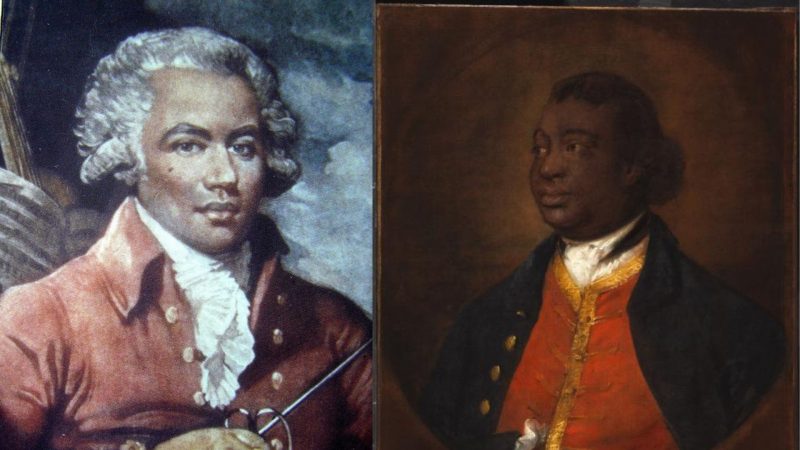

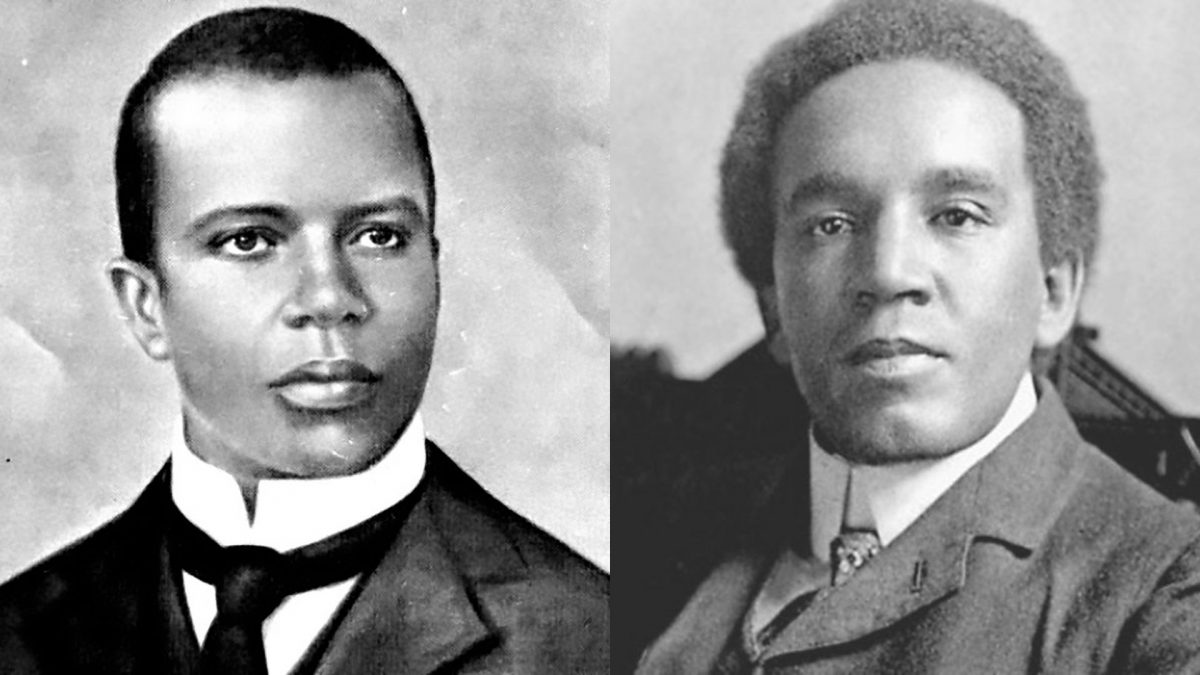

Scott Joplin and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Classical music has a long and detailed history, which regularly includes works by some of the greatest composers ever to have lived, from Bach to Beethoven, Mozart to Mahler. There are many great composers, however, who are unfairly left out of the history books despite their valuable and important contributions to classical music. This October, we celebrate some of history’s most significant black composers – this week, Scott Joplin (c. 1867-1917) and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912).

Scott Joplin was an American composer and pianist, widely known as the ‘King of Ragtime’ and most famous for ‘The Entertainer’ and ‘Maple Leaf Rag’.

Born on the Texas-Arkansas border around 1867, he grew up as the second of six children in a family of railway workers. His parents were both musically talented: his father, Giles, was a former slave from North Carolina and played the violin at plantation parties, whilst his mother, Florence Givens, was a freeborn African-American who worked as a cleaner, singing and playing banjo in her free time. Florence encouraged Scott’s musical talent as a child and encouraged him to play piano while she cleaned.

In his early twenties, Joplin left the railroads to travel the Southern States as a touring musician, and in 1893 he attended the World’s Fair in Chicago. The Fair minimised the involvement of African-Americans, but this didn’t deter black performers from attending, playing to patrons of the saloons and cafés that lined the fair. Joplin formed his own band to play at the Fair, arranging music and playing cornet. The exact circumstances are little documented, but many pinpoint the World’s Fair as the catalyst for ragtime’s explosion into popularity.

Joplin moved to Missouri in 1894, where he worked as a piano teacher and taught future ragtime composers including Arthur Marshall and Scott Hayden. He began publishing music in 1895, and his first rag ‘Original Rags’ was published in 1897 – the same year as William Krell’s ‘Mississippi Rag‘. Joplin’s ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ was published in 1899, projecting him to fame and strongly influencing other ragtime composers. The publishing contract entitled Joplin to a measly 1% royalty on all sales. The first print-run of 400 copies would have earned Joplin approximately $4, roughly equivalent to $125 in 2020. Later sales were more prosperous and the royalties would have covered Joplin’s expenses, although he never replicated this success and did struggle financially for much of his life. It has widely been claimed that the ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ was the first piece of instrumental music to sell over one million copies, and it was this piece that earned him the title of ‘King of Ragtime’.

Joplin moved to St. Louis in 1901 where he continued to compose, publish and perform. His first opera, A Guest of Honor, was confiscated in 1903 along with other belongings after he missed bill payments – tragically, it has never been recovered.

Seeking a producer for a new opera, Joplin moved to New York City in 1907. When his search turned out to be fruitless, he took the financial burden upon himself and published Treemonisha. The premier was only performed in part in 1915 to a small audience in a Harlem rehearsal hall, with Joplin accompanying performers on piano. Hugely unsuccessful, the opera was declaimed as a ‘miserable failure’ by critics, and was never performed again during his lifetime.

In 1916, Scott Joplin’s health was rapidly on the decline as he displayed symptoms of dementia due to syphilis. He was institutionalised in January 1917, and died three months later at the age of 48. He was buried in a pauper’s grave that went unmarked for 57 years.

Joplin’s music returned to popularity in the early 1970s, when Joshua Rifkin recorded an album championing Joplin’s rags. In 1973, The Sting featured several of Joplin’s pieces on its soundtrack, including an orchestral adaptation of ‘The Entertainer’ by Marvin Hamlisch as its theme tune. The film went on to win the Academy Award (Oscars) for Best Picture, projecting ‘The Entertainer’ into popularity. It was in this year that Joplin’s grave was finally marked with a headstone. The opera Treemonisha was finally staged and produced in full in 1972 to critical acclaim, and in 1976 Scott Joplin was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his contributions to American Music.

Across the Atlantic, a contemporary of Scott Joplin was taking a quite different path. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) was born in 1875 in Holborn, London to an English mother, Alice Hare Martin and Dr. Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, a Sierra Leone native who had studied medicine in London. They were unmarried, and Daniel returned to Africa without any knowledge of Alice’s pregnancy. When Samuel was born, Alice named her son Coleridge-Taylor after the late English poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Coleridge-Taylor was brought up by his mother and grandfather in Croydon. His mother’s family were musical, and his grandfather taught him to play the violin from a young age before paying for lessons when the young musician showed exceptional ability. The family arranged for Coleridge-Taylor to study at the Royal College of Music from the age of 15 where he changed from violin to composition. After his graduation, he was appointed professor of the Crystal Palace School of Music and conductor of the Croydon Conservatoire Orchestra.

Coleridge-Taylor’s career as a composer was incredibly successful. Mentored by the music critic August Jaeger and iconic English composer Edward Elgar, Coleridge-Taylor’s ‘Ballade in A minor’ was premiered at the Three Choirs Festival in 1898. In the same year, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast – the first in a trilogy of cantatas – was premiered at the Royal College of Music, conducted by his former teacher Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.

As a young adult, Coleridge-Taylor became interested in his racial heritage on his father’s side, and he participated in the 1900 First Pan-African Conference in London. Here, he made connections with leading American scholars including the activist W.E.B. Du Bois and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Throughout his career, Coleridge-Taylor made several tours to the United States, beginning in 1904 when he was met by then-President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House. Coleridge-Taylor strengthened his relationship with Dunbar, setting his poems to music and hosting a joint recital in London. Dunbar encouraged the composer to draw on his ancestry in his classical compositions, in a similar manner to the way Brahms and Dvořák had drawn inspiration from Hungarian and Bohemian traditional music, respectively.

Aside from his flourishing career, Coleridge-Taylor found love when he met Jessie Walmisley, a fellow student six years his elder at the Royal College of Music. Her parents initially objected to their relationship because of Coleridge-Taylor’s biracial heritage, but later relented and were present at the wedding. Their first child was born the year after their marriage – a son named Hiawatha – followed by their daughter Gwendolyn Avril in 1903. Both children went on to be successful musicians, and Coleridge-Taylor’s daughter forged her own career as a conductor and composer under the pseudonym Avril Coleridge-Taylor.

Despite his immense success and prolific output as a composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor struggled financially throughout his life. His cantata trilogy Song of Hiawatha was widely performed and much-loved, but he didn’t receive a single penny in royalties after selling the rights to the music early on in his career. The stress of this situation is widely thought to have been the trigger for the composer’s pneumonia, which ultimately resulted in his death after collapsing at a train station in 1912, aged just 37.

This was not the end of his legacy, however. After his death, King George V granted his widow an annual pension of £100 – around £11,500 in 2020 – a testament to Coleridge-Taylor’s impact during his lifetime. A further memorial concert was hosted at the Royal Albert Hall, raising £300 for the composer’s family. In recognition of the financial strain that had so greatly contributed to Coleridge-Taylor’s ill health, a campaign was launched to ensure that composers were fairly compensated for the performance, publication and distribution of their works. The result was the formation of the Performing Rights Society – now known as PRS for Music – who are to this day responsible for representing musicians’ rights and collecting royalties on their behalf.