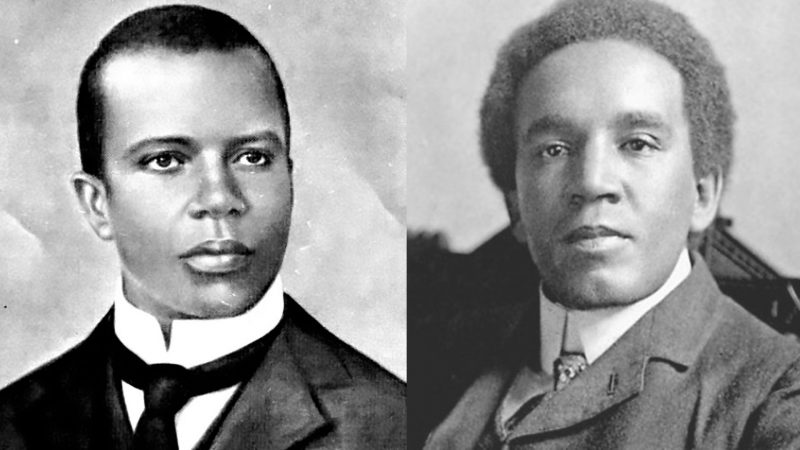

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges and Ignatius Sancho

Classical music has a long and detailed history, which regularly includes works by some of the greatest composers ever to have lived, from Bach to Beethoven, Mozart to Mahler. There are many great composers, however, who are unfairly left out of the history books despite their valuable and important contributions to classical music. This October, we celebrate some of history’s most significant black composers, beginning with Ignatius Sancho (c. 1729-1780) and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799).

Charles Ignatius Sancho was born on a slave ship around 1729 and was orphaned by the age of two – his mother died shortly after his birth, and his father took his own life rather than be forced into slavery. The two-year-old was brought to England, where he was given to three sisters who lived together in Greenwich, London. Reports of his early life are difficult to verify, but at some point he came into contact with a powerful family of aristocrats who lived nearby – the Montagu family. When Sancho was threatened with being sent to the Caribbean to work on a plantation, he fled to the Montagu family for protection. There, he found employment as a butler, and immersed himself in music, poetry, reading and writing.

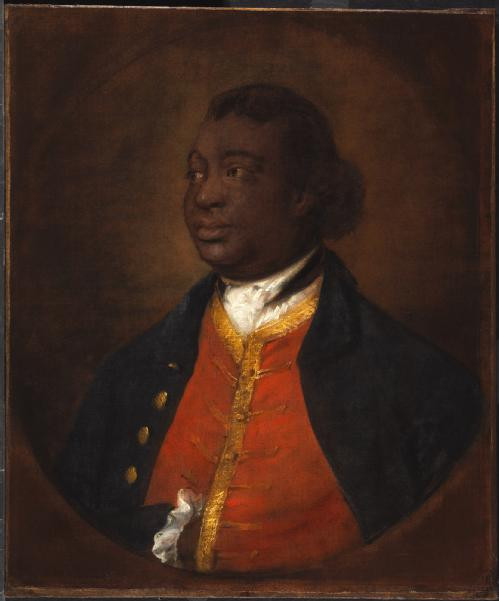

Sancho’s connection with the Montagu family granted him access to their overflowing libraries, as well as a constant stream of influential visitors – one of whom was the prolific painter Thomas Gainsborough, renowned for his portraits and landscapes, and a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts. Gainsborough visited the Montagu house to paint the portrait of the Duchess of Montagu, and asked Sancho to sit for a portrait too.

By the 1760s, Sancho had a good standing in British society. As the debate over slavery raged on in Britain, Sancho wrote to the acclaimed writer Laurence Sterne, urging him to use his literary finesse to make some real change and lobby for the abolition of slavery – an exchange which earned Sancho a reputation as a ‘man of letters’, and brought him into the public eye. Sancho was an accomplished writer, and frequently wrote to newspaper editors, advocating for abolition.

In 1774, Sancho opened a greengrocery store in Westminster where he sold tobacco, sugar, and tea, amongst other things, which were mostly produced by slaves in the West Indies. His position as a shopkeeper allowed him more free time, which he spent writing and publishing a book – Theory of Music – as well as two plays. His newfound status as a financially independent property owner also made him eligible to vote in the 1774 and 1780 general elections. This was no mean feat, since strict legislation meant that only 3% of the entire British population qualified to vote. He was in fact the first black person to vote in a British general election.

Sancho is also widely believed to be the first composer of African descent to publish music in the European tradition. His music was likely performed at private parties hosted by the Montagus, and possibly even at gatherings of black servants. Sancho’s music was published anonymously, but the title page of one of his remaining scores stated that the music within had been ‘Composed by an African’, whilst also highlighting his connections to English nobility by dedicating the work to Henry, Duke of Buccleuch, who had married into the Montagu family.

Over in France, a contemporary of Sancho’s was forging his own career as a musician. Born in Guadeloupe on Christmas Day 1745, Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges was the son of a wealthy plantation owner (later to become French nobility) and his wife’s African slave, Anne Nanon.

Although his father was unable to pass on his title to his illegitimate son, he did claim his son as his own, naming him Chevalier de Saint-Georges. When the younger Saint-Georges was only two, his father was wrongly accused of murder and fled to France with Saint-Georges and Anne. He was later granted a royal pardon, and the family returned to Guadeloupe. When Saint-Georges was twelve years old he was sent to France to be educated. He was joined by his mother and father two years later, as the elder Saint-Georges installed mother and son in an apartment in central Paris, before returning to his estates. As a young boy, Saint-Georges trained as a champion fencer and later went on to fight in the first all-black regiment in Europe during the French Revolution.

His early life as a musician is little documented, but it is evident from his later proficiency as a violinist and composer that he must have received a significant amount of training as a young boy. The first recorded evidence of his musical abilities is found in Antonio Lolli’s two violin concertos (1764) which were composed especially for Saint-Georges, as well as a set of string trios by the French composer François-Joseph Gossec, dedicated to Saint-Georges in 1766.

In 1769, Saint-Georges made his debut as a performer in Gossec’s new orchestra, Le Concert des Amateurs. As little as three years later, in 1772, he emerged as a sensational soloist and composer, performing two of his own violin concertos as Gossec conducted the orchestra. In 1773, Gossec departed the orchestra and appointed Saint-Georges as its new director. Going from strength to strength under the baton of Saint-Georges, the orchestra went on to be renowned as one of the best symphony orchestras in Paris, if not the whole of Europe.

In 1776, a proposal was made to make Saint-Georges the Music Director of the prestigious Paris Opéra – however, four of the leading ladies at the time banded together to block his appointment. In a petition to Queen Marie-Antoinette, they complained that being made to ‘submit to the orders’ of a mixed-race man would “degrade their honour and delicate conscience”. As a result, the proposal was retracted, and Louis XVI nationalized the Opera to avoid scandal.

Saint-Georges went on to be the Music Director of the Duke of Orléans’ private theatre and later founded a new orchestra – the Concert de la Loge Olympique – which was part of an exclusive freemason club. The orchestra became immensely successful, and Saint-Georges even commissioned Austrian composer Franz Joseph Haydn to write six Paris symphonies for the orchestra.

Over the course of his life, Saint-Georges’ compositional output was nothing short of prolific. His surviving works include seven operas, two symphonies, fourteen violin concertos, and plenty of works for various chamber and vocal groups.

Further information:

- Ignatius Sancho as a writer and abolitionist (via Independent)

- Black History Month biography for Ignatius Sancho

- Black Classical Music: The Forgotten History, on BBC 4 with Lenny Henry and Suzy Klein

- ‘In Search of the Black Mozart’ on BBC Radio 4, presented by Chi-chi Nwanoku

- Chevalier de Saint-Georges, Mozart, and the Magic Flute (via Independent)

- More of Saint-Georges’ music (via Medium)