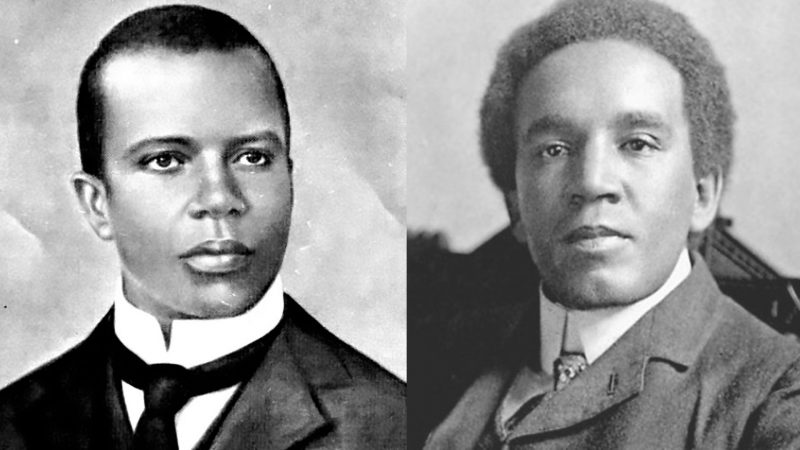

Florence Price

Florence Price

Classical music has a long and detailed history, which regularly includes works by some of the greatest composers ever to have lived, from Bach to Beethoven, Mozart to Mahler. There are many great composers, however, who are unfairly left out of the history books despite their valuable and important contributions to classical music. This October, we celebrate some of history’s most significant black composers – this week, Florence Price (9 April 1887 – 3 June 1953).

Florence Price was born in 1887 to Florence and James Smith in Little Rock, Arkansas. Her mother was a music teacher by profession, and prioritised Florence’s musical education – the young prodigy gave her first piano performance aged 4 and was a published composer by the age of 11. At 14, Price graduated as class valedictorian and enrolled in the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. School records show that she initially listed her hometown as ‘Pueblo, Mexico’, passing as Mexican to avoid the racial discrimination that she would face as a mixed-race African American. During her studies, she wrote her first string trio and symphony, before graduating with Honors in 1906 and moving back to Arkansas to teach.

In 1910, Price moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where she became head of the Music Department at what is now Clark Atlanta University – a historically black college. Two years later, she married lawyer Thomas J. Price and moved back to her hometown where his practice was located. Arkansas in the early 20th Century still operated under Jim Crow laws, which enforced segregation and allowed for the oppression and mistreatment of black people. After a string of racial attacks in Little Rock, including a lynching in 1927, Florence and her family left and moved north in the Great Migration to settle in Chicago, Illinois.

Florence Price’s Violin Concerto No. 2, performed by Kelly Hall-Tompkins on violin with the Urban Playground Chamber Orchestra

In Chicago, Price continued her education in music, languages and liberal arts, publishing four pieces for piano in 1928. The family faced financial struggles and, after her husband became abusive, Price filed for divorce.

Left a single mother to her two daughters and son, Florence branched out in her musical career in order to support her family. She began playing the organ to accompany silent films in cinemas, and composed jingles for radio advertisements under a pseudonym. She also moved in with her friend and fellow composer, Margaret Bonds, who had studied at the Coleridge-Taylor Music School. Margaret introduced Florence to the poet Langston Hughes and contralto Marian Anderson. The four became good friends, and continued to work together throughout the rest of their careers.

Price and Bonds both had great success in the 1932 Wanamaker Foundation Awards, with Bonds winning first place in the song category, and Price winning $500 (roughly $9,500 in 2020) for her first place Symphony in E minor, and third place Piano Sonata. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered Price’s symphony the following year, making her the first African-American woman to have a piece performed by a major orchestra.

Florence Price’s Symphony in E minor, performed by the New Black Repertory Ensemble

Much of Price’s work contained rhythms and melodies from African-American folk songs and spirituals, and she was endlessly creative in her style, combining these tunes with the Western classical music tradition she had trained in. She went on to have her music performed by the WPA Symphony Orchestra of Detroit and the Women’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago and was inducted into the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1940 for her work as a composer.

Florence Price died on June 3, 1953, after suffering a stroke at age 66. Sadly, her work was performed less and less frequently following her death, and some of it was lost forever. However, in 2009 a collection of her work was found in a run-down house on the outskirts of St. Anne, Illinois, including two violin concertos and a fourth symphony. In 2018, the music publishing company G. Schirmer announced that they own the exclusive worldwide rights to Price’s complete catalogue, and even acquired more of Price’s lost manuscripts in 2019.